Armistice, Remembrance, and Veterans

- Carl B. Forkner, Ph.D.

- Mar 18, 2018

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 10, 2021

Originally published on November 11, 2017; updated for 2018

World War I. The Great War. The War to end all Wars. The Great World War I. The conflict

that consumed much of the Western world between 1914 and 1918 was referred to by many different names. It was the first time that new “innovations” in warfare were used as primary weaponry–tanks, airplanes, and chemical weapons. On February 4, 2012, the last surviving veteran of World War I passed away–Florence Green of Great Britain, at age 110.

At the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of the year 1918, the armistice that ended WWI took effect. It had been four bloody and destructive years since the assassination in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrillo Princeps lit the powder keg that was Europe. But now, as word spread of the Armistice, adversaries laid down their weapons and gave thanks for the end to the conflict.

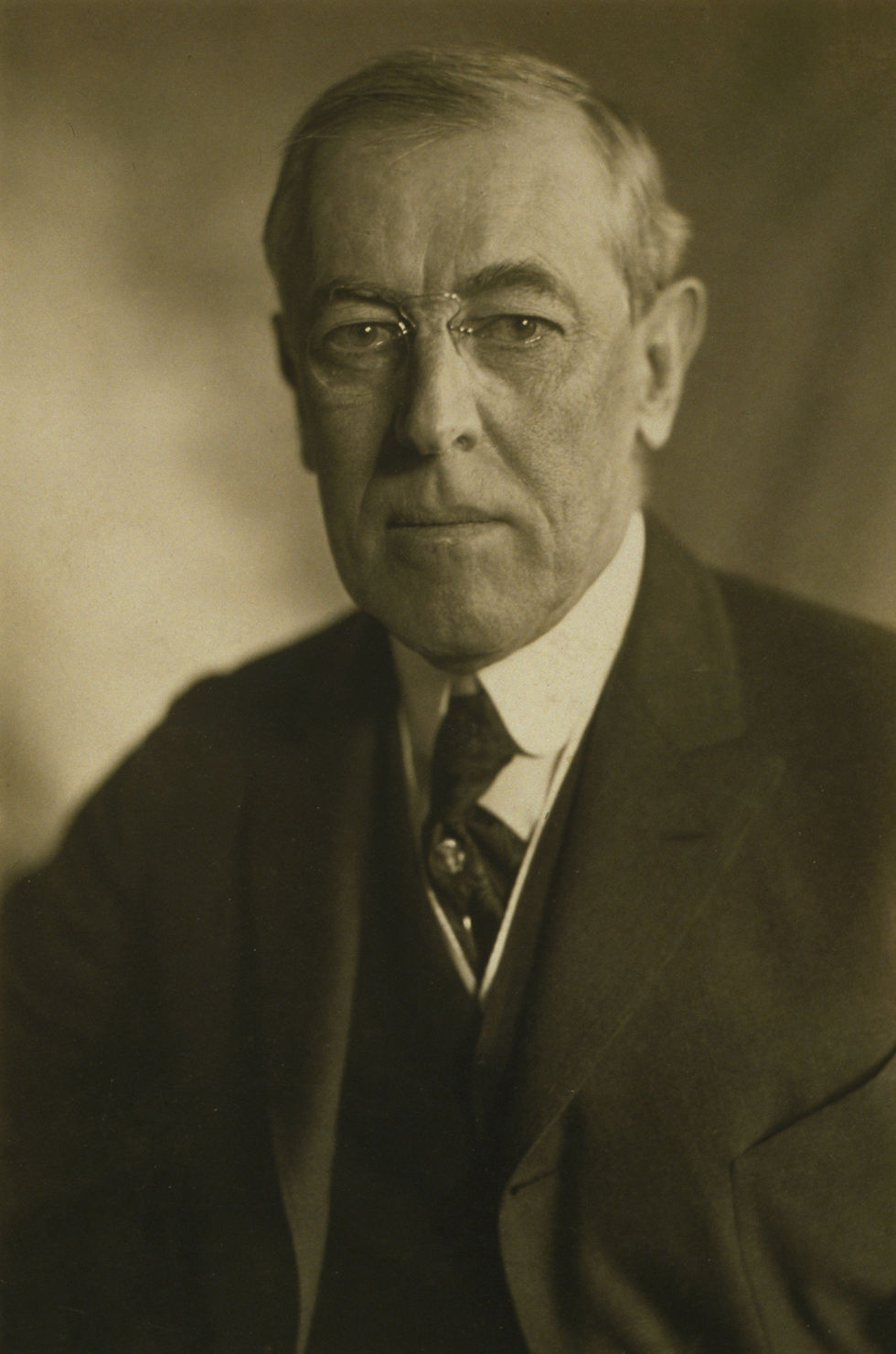

One year later, on November 11, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson addressed Americans from the White House:

A year ago today our enemies laid down their arms in accordance with an armistice which rendered them impotent to renew hostilities, and gave to the world an assured opportunity to reconstruct its shattered order and to work out in peace a new and juster set of inter national relations. The soldiers and people of the European Allies had fought and endured for more than four years to uphold the barrier of civilization against the aggressions of armed force. We ourselves had been in the conflict something more than a year and a half.

– With splendid forgetfulness of mere personal concerns, we re modeled our industries,

concentrated our financial resources, increased our agricultural output, and assembled a great army, so that at the last our power was a decisive factor in the victory. We were able to bring the vast resources, material and moral, of a great and free people to the assistance of our associates in Europe who had suffered and sacrificed without limit in the cause for which we fought. Out of this victory there arose new possibilities of political freedom and economic concert. The war showed us the strength of great nations acting together for high purposes, and the victory of arms foretells the enduring conquests which can be made in peace when nations act justly and in furtherance of the common interests of men. To us in America the reflections of Armistice Day will be filled with – solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country’s service, and with gratitude for the victory, both because of the thing from which it has freed us and because of the opportunity it has given America to show her sympathy with peace and justice in the councils of nations. [1]

History of the Day

Armistice Day

The United States Congress adopted a resolution on June 4, 1926, requesting that President Calvin Coolidge issue annual proclamations calling for the observance of November 11 with appropriate ceremonies. A Congressional Act (52 Stat. 351; 5 U.S. Code, Sec. 87a) approved May 13, 1938, made the 11th of November in each year a legal holiday: “a day to be dedicated to the cause of world peace and to be thereafter celebrated and known as ‘Armistice Day’.” [2]

In 1945, World War II veteran Raymond Weeks from Birmingham, Alabama, had the idea to expand Armistice Day to celebrate all veterans, not just those who died in World War I. Weeks led a delegation to Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, who supported the idea of National Veterans Day. Weeks led the first national celebration in 1947 in Alabama and annually until his death in 1985. President Reagan honored Weeks at the White House with the Presidential Citizenship Medal in 1982 as the driving force for the national holiday. Elizabeth Dole, who prepared the briefing for President Reagan, determined Weeks as the “Father of Veterans Day.” [3]

U.S. Representative Ed Rees from Emporia, Kansas, presented a bill establishing the holiday through Congress. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, also from Kansas, signed the bill into law on May 26, 1954. It had been eight and a half years since Weeks held his first Armistice Day celebration for all veterans. [4]

Veterans Day

Congress amended the bill on June 1, 1954, replacing “Armistice” with “Veterans,” and it has been known as Veterans Day since. [5].

The National Veterans Award was also created in 1954. Congressman Rees of Kansas received the first National Veterans Award in Birmingham, Alabama, for his support offering legislation to make Veterans Day a federal holiday.

Although originally scheduled for celebration on November 11 of every year, starting in 1971 in accordance with the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, Veterans Day was moved to the fourth Monday of October (Oct 25, 1971; Oct 23, 1972; Oct 22, 1973; Oct 28, 1974; Oct 27, 1975; Oct 25, 1976 and Oct 24, 1977). In 1978, it was moved back to its original celebration on November 11. While the legal holiday remains on November 11, if that date happens to be on a Saturday or Sunday, then organizations that formally observe the holiday will normally be closed on the adjacent Friday or Monday, respectively.

Proper Reference

While the holiday is commonly printed as Veteran’s Day or Veterans’ Day in calendars and advertisements (spellings that are grammatically acceptable), the United States Department of Veterans Affairs website states that the attributive (no apostrophe) rather than the possessive case is the official spelling “because it is not a day that ‘belongs’ to veterans, it is a day for honoring all veterans.” [6]

The Poppy

The remembrance poppy was inspired by the World War I poem “In Flanders Fields“. Its opening lines refer to the many poppies that were the first flowers to grow in the churned-up earth of soldiers’ graves in Flanders, a region of Belgium.[2]It is written from the point of view of the dead soldiers and, in the last verse, they call on the living to continue the conflict.[3] The poem was written by Canadian physician, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, on 3 May 1915 after witnessing the death of his friend, a fellow soldier, the day before.

In 1918, Moina Michael, who had taken leave from her professorship at the University of

Georgia to be a volunteer worker for the American YWCA, was inspired by the poem and published a poem of her own called “We Shall Keep the Faith”. In tribute to McCrae’s poem, she vowed to always wear a red poppy as a symbol of remembrance for those who fought and helped in the war. At a November 1918 YWCA Overseas War Secretaries’ conference, she appeared with a silk poppy pinned to her coat and distributed 25 more to those attending. She then campaigned to have the poppy adopted as a national symbol of remembrance. At a conference in 1920, the National American Legion adopted it as their official symbol of remembrance. At this conference, Frenchwoman Anna E. Guérin was inspired to introduce the artificial poppies commonly used today. In 1921 she sent her poppy sellers to London, where the symbol was adopted by Field Marshal Douglas Haig, a founder of the Royal British Legion. It was also adopted by veterans’ groups in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. James Fox notes that all of the countries who adopted the remembrance poppy were the “victors” of World War I [6].

Today, remembrance poppies are mostly used in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand—countries which were formerly part of the British Empire—to commemorate their servicemen and women killed in all conflicts. They are used to a lesser extent in the United States.

To all who served–less than 7% of Americans–I offer my heartfelt thanks and respect.

To our Allied veterans around the world, my thanks and respect and hopes for a meaningful Remembrance Day.

Although it is the formal motto of the United States Navy, I believe that those who are serving and have served fall under the same philosophy:

non sibi sed patriae (not self, but country)

Hooah! Aim High! Semper Paratus! Semper Fidelis! Semper Fortis!

________________________________________

[1] “Supplement to the Messages and Papers of the Presidents: Covering the Second Term of Woodrow Wilson, March 4, 1917, to March 4, 1921”. Bureau of National Literature. 11 November 2015.

[2] “Veterans Day History”. Veteran’s Affairs.

[3] Zurski, Ken (November 11, 2016). “Raymond Weeks: The Father of Veterans Day”. Unremembered History.

[4] Carter, Julie (November 2003). “Where Veterans Day began”. VFW Magazine. Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14.

[5] “History of Veterans Day”. United States Department of Veterans Affairs. 2007-11-26.

[6] Veterans Day Frequently Asked Questions, Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated 2015-07-20.

Comments